Microplastics have been found in the land, sea and air and across the food chain. These extremely tiny plastic particles are not only contaminating the environment but also posing serious threats to human health. Earlier, microplastics were found in human blood, heart and other organs. Now scientists have found evidence of microplastics in our brains. It is estimated that the average person can eat, drink or breathe between 78,000 and 2,11,000 microplastic particles every year. Other studies indicate an average human ingest about 5 grams of plastic every week.

Microplastics have infiltrated from the water we drink to the food we consume. A recent study conducted by Toxics Link, an environmental research organisation, has revealed the alarming presence of microplastics in every salt and sugar brand tested in India. The research examined 10 types of salt, including table, rock, sea, and local varieties, as well as five types of sugar purchased from both online and physical stores. These tiny plastic particles varied in shape, including fibres, pellets, films, and fragments, with sizes ranging from 0.1 to 5 millimetres. Iodised salt emerged as the most contaminated, with 89.15 microplastic pieces per kilogram, while organic rock salt had the lowest levels at 6.70 pieces per kilogram.

A Call for Swift Global Action

It’s been 20 years since a paper in the journal Science showed the environmental accumulation of tiny plastic fragments and fibres. It named the particles “microplastics”. The paper opened an entire research field. Since then, more than 7,000 published studies have shown the prevalence of microplastics in the environment, in wildlife and in the human body. Microplastics are pervasive in food and drink and have been detected throughout the human body. Evidence of their harmful effects is emerging at every level of biological organisation, from tiny insects at the bottom of the food chain to apex predators.

In a recent article published in the journal Science, summarising the effects of microplastics on the environment and human health, scientists alarmed that a collective global action is urgently needed to tackle microplastics – and the problem has never been more pressing. While public concern and international efforts to address microplastic pollution are growing, significant scientific uncertainties remain, particularly in evaluating long-term impacts and the effectiveness of proposed interventions.

Some countries have implemented laws regulating microplastics. But this is insufficient to address the huge challenge. The UN’s Global Plastics Treaty, which is a legally binding agreement, offers an important opportunity. The fifth round of negotiations will begin in November 2024. The treaty aims to reduce global production of plastics. But the deal must also include measures to reduce microplastics specifically. Individuals and communities must be brought on board to drive support for government policies. After 20 years of microplastics research, we have more than enough evidence to act now.

What are Microplastics?

Microplastics are tiny plastic particles less than 5 millimetres in size. They originate from various sources, including the breakdown of larger plastic items, the shedding of synthetic fibres from clothing, and the use of certain personal care products. Some – such as microbeads, added to cosmetics and toiletry products – are small, while other plastic gradually breaks down to this size.

Due to their small size, microplastics can easily enter ecosystems, posing risks to wildlife and potentially accumulating in the food chain. They are found in oceans, rivers, soil, and even in the air, raising concerns about their impact on health and the environment. According to UNEP, up to 23 million tonnes of plastic waste leaks into the world’s water systems every year.

By 2040, microplastics releases to the environment could more than double. Even if humans stopped the flow of microplastics into the environment, the breakdown of bigger plastics would continue.

Studies have identified some of the main sources of microplastics as–cosmetic cleansers, synthetic textiles, vehicle tyres, plastic-coated fertilisers, plastic film used as mulch in agriculture, fishing rope and netting, crumb rubber infill used in artificial turf and plastics recycling.

Infiltration in Food Chain

Microplastics can settle in sediments at the bottom of water bodies. Organisms living in or on the sediment, like certain crustaceans and worms, can ingest these particles. Marine animals, such as fish, shellfish, and plankton, can mistake microplastics for food. When they consume these particles, microplastics can accumulate in their bodies. In aquaculture and fishing, microplastics can be transferred to human food products when contaminated fish or shellfish are harvested and processed for consumption.

These tiny particles are often small enough to pass through water filtration systems, and we can then unknowingly ingest them. Microplastics can also be present in soil, often from agricultural runoff or the use of compost that contains plastic debris. Soil organisms, such as earthworms, can ingest these particles. Microplastics can be airborne and eventually settle on crops or in water sources, leading to potential ingestion by both animals and humans. Microplastics have been detected in more than 1,300 animal species, including fish, mammals, birds and insects.

Studies have found that people can ingest microplastics directly, including through crops, fish and plastic food containers, which could leach microplastics into the food they hold. Microplastics have been found in foodstuffs including honey, tea and sugar, as well as in fruit and vegetables. Such widespread and long-term exposure makes this a serious concern for human health.

Invaders in Our Bodies

Microplastics have been found in human brain tissue above the nose, after already being discovered in nearly every organ in the human body, according to a new study published in the journal JAMA Network Open. Researchers analysed the brains of 15 cadavers—12 men and three women who died between the ages of 33 and 100—and found eight contained microplastics in the tissue of the olfactory bulb, the part of the brain that processes smell. Early findings in a study published in August suggested the brain contained up to 30 times more microplastic than other organs. The researchers also found the number of plastics in brain samples increased by about 50 per cent between 2016 and 2024. This may reflect the rise in environmental plastic pollution and increased human exposure.

The most common type of plastic found in human brain was polypropylene, followed by polyamide, nylon and polyethylene vinyl acetate. Polypropylene is often used in manufacturing furniture, clothing, rugs or packaging for cleaning products. Polyamide and nylon are similar microplastics and are both often used for textiles like clothing and carpets. Polyethylene vinyl acetate is used as a flexible plastic for manufacturing goods like adhesives, paints or plastic wrap.

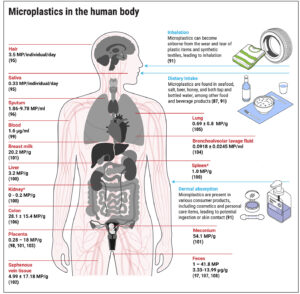

Apart from human brain, microplastics have been found in human blood, hearts, the reproductive systems of men, lungs and liver tissues, mother’s milk and the placenta, among other organs.

Some studies have linked microplastics to lung inflammation and a higher risk of lung cancer, metabolic disorders, neurotoxicity, endocrine disruption, weight gain, insulin resistance and decreased reproductive health. One study published earlier this year linked higher mortality rates to people with high levels of microplastics in their arteries. A 2024 study from the University of California, San Diego, found that microplastic particles can enter the body and activate autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Moreover, exposure to microplastics can heighten the chances of developing heart disease, cancer, and respiratory disorders.

How to Minimise Exposure to Microplastics?

Microplastic pollution is the result of human actions. We created the problem and we should create the solution. Minimizing exposure to microplastics involves both individual choices and broader lifestyle changes. Here are some effective strategies:

- Reduce Plastic Use: The best thing we can do is reduce producing plastic waste, so less ends up in the environment. Avoid foods and drinks packaged in single-use plastic or reheated in plastic containers. Opt for reusable bags, containers, and bottles. Choose products with minimal or no plastic packaging.

- Choose Natural Fibers: When buying clothing, select items made from natural materials like cotton, wool, or linen instead of synthetic fibres that shed microplastics during washing.

- Wash Wisely: Use a microfiber filter for your washing machine or wash synthetic clothes less frequently to reduce fibre shedding. Consider washing in cold water, as hot water can increase shedding.

- Filter Drinking Water: Use a high-quality water filter to reduce microplastics in tap water. Be aware that bottled water can also contain microplastics.

- Eat Fresh and Whole Foods: Limit processed and packaged foods, which may contain microplastics. Fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole foods are less likely to be contaminated.

- Avoid Personal Care Products with Microbeads: Check labels for ingredients like “polyethylene” or “polypropylene,” commonly found in scrubs and exfoliants, and choose products without microbeads.

- Be Cautious with Seafood: If concerned about microplastics in seafood, consider sourcing from reputable suppliers and opt for smaller fish that are less likely to accumulate toxins.

- No Waste Dumping in Water Bodies: Refrain from dumping plastic waste into rivers, ponds, and other water bodies.

By making conscious decisions in daily life, you can contribute to minimizing your exposure to microplastics and help reduce their presence in the environment.

Leave a Comment