“I had stood at the place where this baby had been thrown away. Another girl unnamed and unwanted. But seeing Edha here loved and cared for by this family, gave me hope that one day, we will come to cherish all our children”, says Amitabh Parashar in his documentary, beaming with hope while looking at little Edha and her loving parents who adopted her.

Indian Journalist Amitabh Parashar, in his documentary from BBC World Service titled ‘The Midwife’s Confession’ highlights the harrowing issue of female infanticide in Bihar, India. Parashar’s videos capturing the scourge of female infanticide in his home state of Bihar over nearly three decades and a grassroots campaign to fight against the practice form the basis of the new documentary released by the BBC.

An Unwavering Commitment of 30 Years

‘The Midwife’s Confession’, aired on the British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) News channel over two parts, is made up of never-before-seen footage of midwives who assisted home births in and around Katihar in Bihar over 30 years. Their testimonies are the starting point for the documentary to explore the troubling history of infanticide and how social worker Anila Kumari’s campaign to work with the same midwives helped turn the tide.

Amitabh Parashar has been following the story of five rural midwives for 30 years, ever since he went to interview Siro Devi who was one of them, in his home town in Bihar in 1996. The midwives had been identified by a non-governmental organisation (NGO) as being behind the murder of baby girls in the Katihar district where, under pressure from the newborns’ parents, they were killing them by feeding them chemicals or simply wringing their necks.

These midwives featured in a report published in 1995 by an NGO, based on interviews with them and 30 other midwives. According to the report, more than 1,000 baby girls were being murdered every year in one district, by just 35 midwives. Bihar at the time had more than half a million midwives and infanticide was not limited to only Bihar.

No Option to Refuse Orders

During the interview, one of the midwives Hakiya Devi told Amitabh Parashar that refusing orders was almost never an option for a midwife. The family would lock the room and stand behind a midwife with sticks giving order to kill the newborn girl. Having four-five daughters already, they did not want any more girl. She said midwives were scared and executed the orders. Belonging to lower castes, refusing orders of powerful, upper-caste families was unthinkable for the midwives.

The midwives were given small rewards for killing a newborn girl or sometimes not even that. While the birth of a boy earned them good money, the birth of a girl earned them less or none.

The Pernicious Dowry System

The reason for the imbalance between the birth of a boy and a baby girl is steeped in the Indian society’s custom of dowry given in a girl’s marriage. Though the pernicious custom was outlawed in 1961, it continues to the present day. A dowry can be anything – cash, jewelry, utensils, vehicle, as per the financial status of the family or many a times much more than that. For many families, this makes the birth of a son a celebration and the birth of a daughter a financial burden.

The reason for the imbalance between the birth of a boy and a baby girl is steeped in the Indian society’s custom of dowry given in a girl’s marriage. Though the pernicious custom was outlawed in 1961, it continues to the present day. A dowry can be anything – cash, jewelry, utensils, vehicle, as per the financial status of the family or many a times much more than that. For many families, this makes the birth of a son a celebration and the birth of a daughter a financial burden.

When Parashar asks one of the midwives named Siro Devi the real reason for the killings. She says that the real reason is dowry and nothing else. Boys are considered higher, and girls are considered lower, she says.

The preference for sons can be seen in India’s national-level data. The last census in 2011 recorded a ratio of 940 women to every 1,000 men. This is nevertheless an improvement – in the 1991 census, the ratio was 927 per 1,000.

A Silent Change

But slowly the midwives who once carried out these orders had started to resist. This change was initiated by Anila Kumari, a social worker who supported women in the villages around Katihar, and was dedicated to addressing the root causes of these killings. When Anila Kumari came to know about these killings, she designed an awareness programme to persuade the same midwives to bring the babies to her office instead of killing them. Anila’s effort marked a turning point for the midwives featured in the documentary. Anila asked the midwives, “Would you do this to your own daughter?” Her question apparently pierced years of rationalisation and denial.

With Anila’s encouragement, a small group of midwives rescued at least five newborn baby girls whose families wanted them to be killed or had already abandoned them. One girl died, but the other four were sent to an NGO in Patna, Bihar’s capital, and put up for adoption.

During his unwavering commitment of 30 years to follow the story, Journalist Amitabh Parashar tracked down a young woman who is one of the four surviving babies rescued by the midwives in the late 1990s. The woman now named Monica Thatte was adopted from an orphanage in Pune at the age of three, and the documentary follows her journey back to Bihar to meet midwife Siro Devi and social worker Anila Kumari, whose campaign saved her life.

A Documentary worth watching

‘The Midwife’s Confession” shows the shocking confessions of midwives how they routinely murdered new-born baby girls. The documentary aims to raise awareness about female infanticide and promote Anila Kumari’s successful intervention. The midwives can be seen telling Parashar, on camera, how they did not want to kill but the girls’ own families would force them to murder the children. Through the stories of two girls who were saved and adopted- Monica Thatte and Edha Trivedi, the documentary also shows a silver lining after the dark clouds of the midwives’ confessions.

‘The Midwife’s Confession” shows the shocking confessions of midwives how they routinely murdered new-born baby girls. The documentary aims to raise awareness about female infanticide and promote Anila Kumari’s successful intervention. The midwives can be seen telling Parashar, on camera, how they did not want to kill but the girls’ own families would force them to murder the children. Through the stories of two girls who were saved and adopted- Monica Thatte and Edha Trivedi, the documentary also shows a silver lining after the dark clouds of the midwives’ confessions.

The documentary was shot by Journalist Amitabh Parashar over a period of 30 years and produced & directed over the past two years by a team of journalists and filmmakers for BBC Eye Investigations, a global documentary strand from the BBC World Service. The first part of the documentary was aired on September 11 and the concluding part will be aired on September 21. The documentary can also be watched on the YouTube channel of BBC World Service.

Though the documentary highlights the issue of female infanticide of one district in the state of Bihar in India but the issue is not just limited to Bihar and not just to India.

The Missing Baby Girls Worldwide

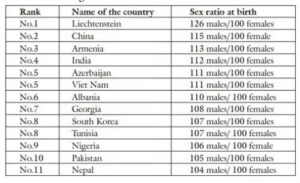

In a first ever global study on female infanticide in 2016 by Asian Centre for Human Rights (ACHR), a Delhi-based NGO dedicated to protection of human rights, it was revealed that preference of son over daughter is a major reason for female infanticide in many countries around the world. Titled “Female Infanticide Worldwide: The case for action by the UN Human Rights Council”, the report makes a continent-wise analysis of infanticide patterns. The report examines female infanticide worldwide with Liechtenstein having the highest skewed sex ratio at birth with 126 males/100 females, followed by China, Armenia, India, Azerbaijan, Vietnam, Albania, Georgia, South Korea, Tunisia, Nigeria, Pakistan and Nepal. Millions of girls go missing each year and as per UNFPA over 170 million girls are missing in Asia alone. In China, 115 boys are born every 100 females, while in India 112 males per 100 females, causing a demographic imbalance.

As per UN (World Population Prospects 2024), out of 237 countries/regions estimated by United Nations, 159 have more females than males. The sex ratio at birth in every country is male-biased, ranging from around 101 to 116 boys per 100 girls. Liechtenstein has the highest male ratio with 116 male births per 100 female births. The sex ratio is the number of males for every 100 females in a population.

Anthropologist Laila Williamson, in “Infanticide: an anthropological analysis” (1978), a summary of data she had collected on how widespread infanticide was, notes that infanticide had occurred on every continent and was carried out by groups ranging from hunter gatherers to highly developed societies, and that, rather than this practice being an exception, it has been commonplace. The practice has been well documented amongst the indigenous peoples of Australia, Northern Alaska and South Asia specially India & China.

Anthropologist Barbara D. Miller argues the practice of female infanticide to be “almost universal”, even in the western world. Miller contends that in regions where women are not employed in agriculture and regions in which gender related vices like dowry/female foeticide/genital mutilation etc are practiced, female infanticide is common. Female infanticide is a major cause of concern in several countries. It has been argued that the “low status” of women in Patriarchal societies creates a bias against females.

In 1871 in ‘The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex’, Charles Darwin wrote that the practice was common among the aboriginal tribes of Australia.

The Perturbing Trend in China and India

China has a history of female infanticide which spans 2,000 years. When Christian missionaries arrived in China in the late 16th century, they witnessed newborns being thrown into rivers or onto rubbish piles. In the 17th century Matteo Ricci documented that the practice occurred in several of China’s provinces and said that the primary reason for the practice was poverty. The practice continued into the 19th century and declined quickly during the Communist era, but re-emerged as an issue since the introduction of the one-child policy in the early 1980s. The 2020 census showed a male-to-female ratio of 105.07 to 100 for mainland China, a record low since the People’s Republic of China began conducting censuses. Confucianism has an influence on female infanticide in China. The fact that male children work to provide for their elderly and that certain traditions are male-driven lead many to believe they are more desirable. Every year in China and India alone, there are close to two million instances of some form of female infanticide.

China has a history of female infanticide which spans 2,000 years. When Christian missionaries arrived in China in the late 16th century, they witnessed newborns being thrown into rivers or onto rubbish piles. In the 17th century Matteo Ricci documented that the practice occurred in several of China’s provinces and said that the primary reason for the practice was poverty. The practice continued into the 19th century and declined quickly during the Communist era, but re-emerged as an issue since the introduction of the one-child policy in the early 1980s. The 2020 census showed a male-to-female ratio of 105.07 to 100 for mainland China, a record low since the People’s Republic of China began conducting censuses. Confucianism has an influence on female infanticide in China. The fact that male children work to provide for their elderly and that certain traditions are male-driven lead many to believe they are more desirable. Every year in China and India alone, there are close to two million instances of some form of female infanticide.

In India, female infanticide has a history spanning centuries. The dowry system has been cited as one of the main reasons for this. The sex ratio of India has steadily declined since 1901. In the Population Census of 2011, the population ratio was 940 females per 1000 of males. Kerala has the highest sex ratio in India (1084), while Haryana is the lowest (879), as per the 2011 census. According to United Nations Population Fund, at the 2011 census enumeration, about four million girls of ages 0-6 may be considered to have been missing; 2.5 million on account of sex selection (pre- natal discrimination) and 1.5 million due to excess female mortality (post-natal discrimination).

According to a United Nations Population Fund report released in 2020, nearly 4.6 crore (45.8 million) females are ‘missing’ in Indian demography in the year 2020, mainly due to pre and post-birth sex selection practices stemming from son preference and gender inequality. India accounts for almost one-third (32.1 per cent) of the total 142.6 million missing females in the world and is the second highest contributor. The biggest contributor is China at 72.3 million (7.2 crore) ‘missing females’ that is 50.7 per cent of all missing females in the world.

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data from 2019-2021 indicates a notable improvement in the sex ratio in India, with 1,020 women for every 1,000 men, marking the highest sex ratio recorded in NFHS surveys since the first modern synchronous census in 1881. NFHS (under Ministry of Health and Family Welfare) provides reliable data regarding population dynamics and health and family welfare.

Improvement in SRB in India

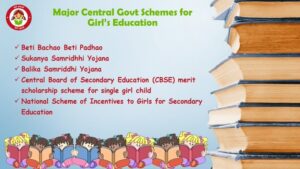

In order to improve the survival and welfare of girls and reverse the distorted sex ratio at birth (SRB) in India, both the central and the state governments have launched special financial incentive schemes for girls. The central government introduced ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’ initiative in 2015 to prevent gender discrimination and to ensure survival, protection and education of girls. Apart from this, central and state governments have started various schemes for the welfare and education of girl child. These schemes aim at improving the value of the girl child on the premise that financial benefits would trigger behavioral changes among parents and communities.

As per NFHS data, the sex ratio at birth (SRB) in India has improved to 933 females per 1,000 males in 2022-23 from 929 females per 1,000 males in 2019-2020. It was 919 females per 1,000 males in 2015-16 and 918 females per 1,000 males in 2014-15. This is a significant improvement and indicates that efforts to address the issue are beginning to have an impact.

The sex ratio at birth in India has begun to improve, which is a positive development. The government’s initiatives and small societal changes have played an important role in addressing the issue of the skewed sex ratio. However, there are still challenges, biggest of all is the Dowry system which has long been abolished but still persists, and is a major cause for female infanticide and foeticide in India. There is still much work to be done to ensure gender equality and eradicate discrimination against girls and women.

Leave a Comment