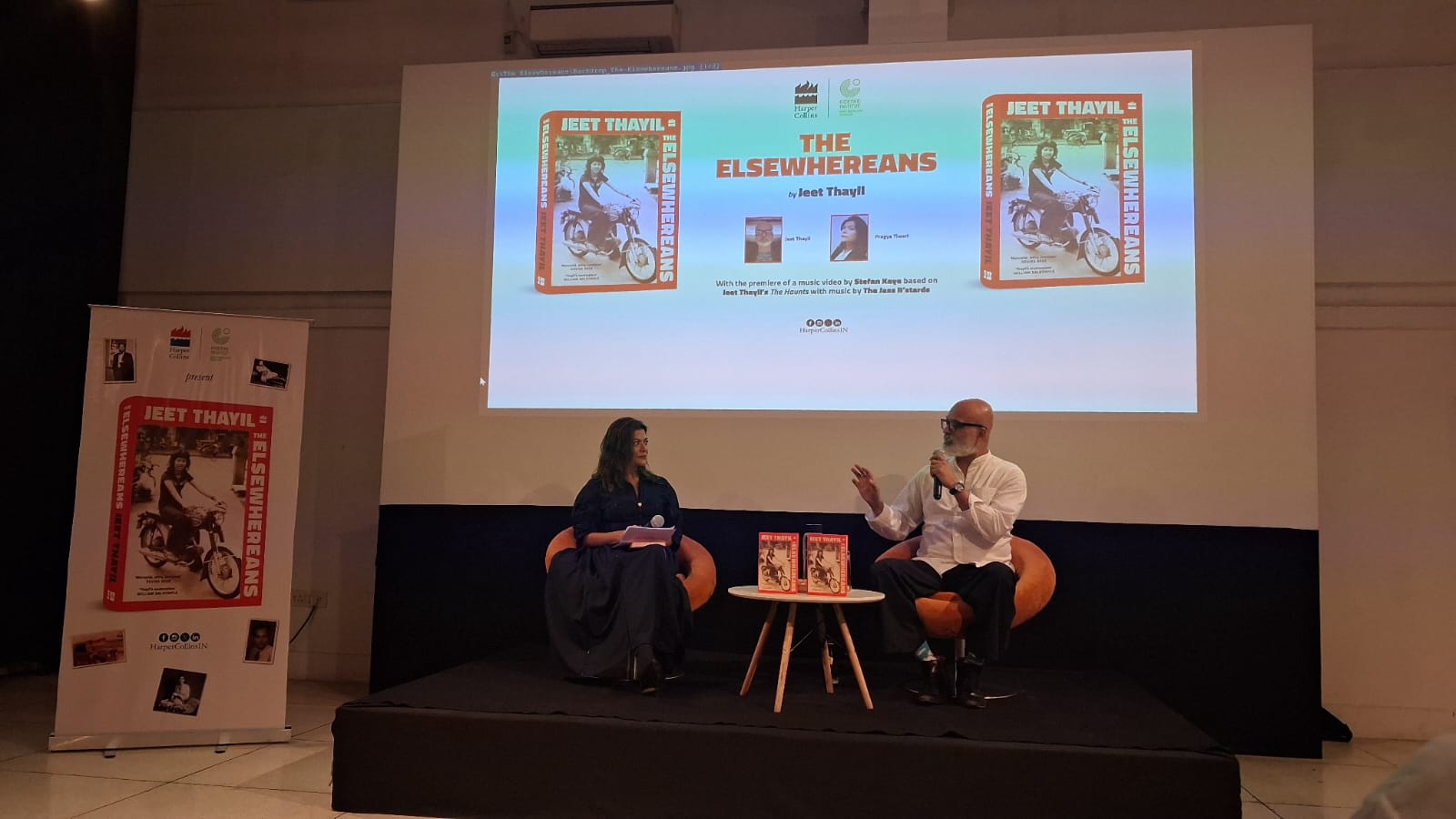

When Jeet Thayil—a Sahitya Akademi Award–winning poet, novelist, librettist, and musician—launches a new book, the literary world takes notice. Known for his Booker Prize–shortlisted debut novel Narcopolis and his lyrical command over both prose and poetry, Thayil has returned with a powerful and genre-defying work: The Elsewhereans.

Fresh off the success of his recent collection I’ll Have It Here, Thayil’s new novel explores a deeply human condition: the ache of belonging “nowhere and everywhere at once.”

A Story Rooted in Exile and Return

At the heart of The Elsewhereans are George and Ammu, characters who long for a sense of home. They choose Kerala as their anchorage, but instead of finding roots, they encounter an even greater sense of dislocation—foreign both to the land and to themselves.

When asked what inspired this figure of the “Elsewherean,” Thayil described it as “the universal absence.” He explained that migration, whether for financial or personal reasons, creates this feeling of being foreign everywhere:

“Movement and absence are the modern equalizers. Who among us doesn’t feel ‘foreign’, even when we live in a place we consider home? You can’t step in the same river twice. It’s not the same river and you’re not the same person.”

This riverine imagery runs through the book, weaving themes of memory, loss, and belonging into a poetic current.

Family, Memory, and Silence

The Elsewhereans is also Thayil’s most personal work yet, drawn from his own family history. Writing such a novel came with an acute sense of responsibility—not just to art, but to memory.

He admitted that he sought permission from his parents before incorporating their likenesses into the book:

“My father gave his permission willingly, my mother reluctantly. She’d probably agree with the epigraph that begins The Elsewhereans: ‘When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.’”

But perhaps what shapes memory most powerfully are not the stories families tell, but the silences they keep. Thayil reflected:

“Silence is power. In my family, much of the personal history was left unsaid, particularly when it came to tragedy… Why hush up a death? Or pass over the circumstances of loss?”

In The Elsewhereans, those silences echo between the lines.

Writing as Resistance

The novel meditates on what is remembered and what time erases. Through fragmented stories of Ammu, Thomas, Chachiamma, Nguyen Phuc Chau, and Da Nang, Thayil questions the existential irony of life: every existence is a story, yet most are lost to time.

For him, writing is an act of defiance:

“A poem is an act of resistance against time and its tyrannies. It uses time (meter, rhyme, rhythm) to resist its passing. If you don’t do it, no one will. Only you can tell this story.”

This makes The Elsewhereans not just a family narrative but a universal archive of loss, remembrance, and belonging.

A Hybrid Form: Between Memoir, Fiction, and Ghost Story

True to Thayil’s style, The Elsewhereans resists simple categorization. It moves fluidly between novel, memoir, travelogue, ghost story, and even photo archive. But this hybrid form, he insists, emerged organically:

“I started with a more conventional, linear narrative. Then it all changed. Rather than linearity, The Elsewhereans is circularity—of time and memory. Motifs, places, names, characters return. The last chapters are titled ‘Return and End’ and ‘End and Return’.”

The result is a narrative structure that mirrors the ebb and flow of memory itself.

Why The Elsewhereans Matters

At its core, Jeet Thayil’s new book is about displacement, memory, and the search for anchorage in a shifting world. It resonates with anyone who has ever felt out of place, even in their own homeland.

From Narcopolis’s hallucinatory streets of Bombay to The Elsewhereans’s deeply personal meditations, Thayil continues to prove why he is one of India’s most important literary voices today—pushing the boundaries of genre, language, and memory.

The Elsewhereans is not just a novel. It is a river of voices, a meditation on exile, and a testament to the act of writing as resistance.

Leave a Comment